A new paper from the Office of Disease Prevention (ODP) reports that the level of support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for prevention research on the leading risk factors and causes of death and disability in the United States falls well below their burden on the nation's health. The study appears in JAMA Network Open. The portfolio analysis defines prevention research as primary or secondary prevention research in humans, together with related methods research, and was restricted to grants and collaborative agreements funded through the NIH extramural research program in fiscal years 2012–2017.

In addition to looking at how the NIH prevention research portfolio aligned with these leading risk factors and causes of death and disability, we examined what study designs were used, populations were targeted, and types of prevention research were evaluated in the context of these risk factors and causes. We also describe how often risk factors or diseases co-occur in the same study. Finally, we outline opportunities for the NIH to better align prevention research topics with their burden on Americans.

Levels of NIH Prevention Research Compared to Disease Burden in the United States

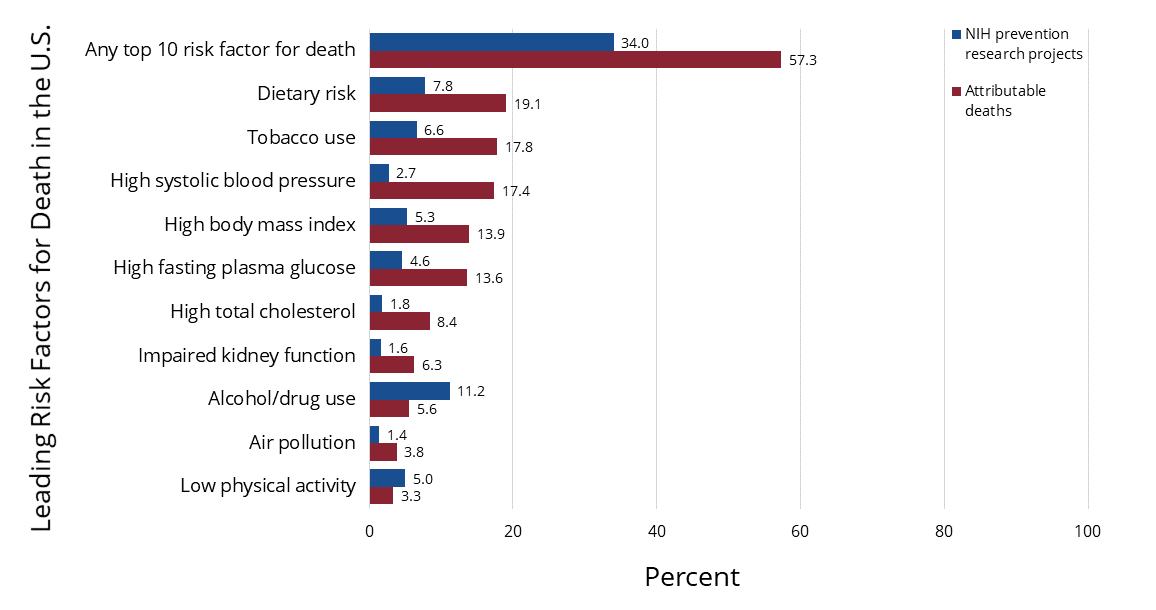

More than half of the deaths in the United States are attributable to the top 10 risk factors for death, yet we found that just a third of the prevention research projects supported by the NIH focus on these risk factors. Similarly, while seven out of every 10 Americans die from the 10 leading causes of death, fewer than three in 10 NIH-supported prevention research projects study these causes of death. Overall, only about half of the NIH prevention research portfolio measures at least one leading risk factor or cause of death and disability in the United States. If we put this into the context of the NIH portfolio of grants and cooperative agreements overall, this means that only 8.5% of all NIH-funded grants and cooperative agreements are focused on preventing the leading risk factors or causes of death and disability.

While disease burden is one of many factors the NIH considers when making funding decisions, it also has limited resources and many worthy targets. NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs) have the difficult task of prioritizing the research they fund based on public health needs, scientific opportunities, the quality of the applications submitted, and the priorities of their IC.

|

Leading Risk Factors for Death in the United States

|

Leading Causes of Death in the United States

|

|---|---|

| Dietary risk | Heart disease |

| Tobacco | Cancer |

| High systolic blood pressure | Accidents |

| High body mass index | Chronic lower respiratory disease |

| High fasting plasma glucose | Stroke |

| High total cholesterol | Alzheimer's disease |

| Impaired kidney function | Diabetes |

| Alcohol/drug use | Influenza/Pneumonia |

| Air pollution | Kidney disease |

| Low physical activity | Suicide |

Intervention Studies on Leading Risk Factors or Causes of Death

The ODP’s analysis found that 60% of NIH-funded prevention research examining the leading risk factors and causes of death and disability in the United States included observational studies and just over 45% included analyses of existing data. Far fewer–24.6%–prevention research projects included randomized trials to evaluate interventions that may actually prevent the leading risk factors and causes for death. When a project did include a randomized intervention, it was more common that it measured a risk factor than a cause of death as an outcome.

Because so much is already known about these risk factors and causes, and because randomized intervention trials often provide the strongest evidence for clinical and public health guidelines, greater attention should be given to prevention research that develops and tests interventions to address these risk factors and causes.

Studying Multiple Leading Risk Factors or Causes of Death

Although it is common for one person to have multiple risk factors (for example, people who smoke also often have a poor diet and engage in little physical activity) associated with the leading causes of death, only 3.7% of prevention research projects took advantage of this pattern to address multiple risk factors or causes at the same time.

The nation could benefit significantly if the NIH encouraged more prevention research projects that focus on multiple risk factors or causes of death or disability when possible. Taking this approach could also help the NIH more efficiently use its existing resources.

Details of the Study

Our study combined a machine learning approach and manual coding of awards to characterize 11,082 NIH grants and cooperative agreements awarded between fiscal years 2012–2017. We focused on primary and secondary prevention research in humans, together with related methods research, which is the ODP’s primary focus for prevention research. These areas of research can have a more immediate effect on human health and well-being than basic or preclinical work that could still be years away from preventing disease or disability in the population.

Interested in more publications from ODP staff?

Check out our Staff Publications page.

It is important to note that our portfolio analysis was limited to the most common types of grants and cooperative agreements, so it does not reflect work done in the NIH’s intramural program or through contracts.

The study is now available in the journal JAMA Network Open.